The Music of Modern Times

by Phil Posner ©2001

In the

wake of the many live orchestra performances of Chaplin's films that have

occurred over the past few years, much has been written about Chaplin's talents

as a composer. However, few writers have

attempted to go into detail about what makes Chaplin scores work so well with

his films. This writer has already

written a more generalized article on Chaplin as composer, but in this piece I

intend to explore the music of arguably his best score, that of MODERN TIMES.

It may have been MODERN TIMES that prompted W.C.

Fields to make that well known comment on Chaplin’s dancing abilities (although

it’s just as likely to be THE GREAT DICTATOR).

Indeed parts of the film give the impression of being danced, performed

to the score, rather than having the score composed and conducted to match the

action, which is in fact how it was done.

In an interview which appears on the current DVD version of the film,

David Raksin, Chaplin’s musical assistant and arranger for the film, credits

conductor Alfred Newman with the perfect synchronization, but credit must also

be given to the composer of the score, Chaplin himself. Raksin and others have attested to the fact

that Chaplin was involved in all stages of the composing/arranging/recording

process and nothing went into the soundtrack without his approval.

The score is typical of the style Chaplin was developing (this was only his second attempt at composing a complete score) featuring leit-motifs (reoccurring musical phrases that represent certain characters or ideas), music hall and jazz style tunes and the occasional reference or use of other composer’s themes. There is one hit tune in its inchoate form, the classic “Smile” and also the momentous performance of “Titina” in which Chaplin’s voice is heard on screen for the first time.

The

opening scene

presents us with the first major theme, the discordant, somewhat Gershwinesque

fanfare that proclaims the portrayal of the industrial age with its theme of

authority, industry and hardship. This

theme recurs throughout the film, in varying

moods, as a leitmotif for struggle or the intervention of fate.

The factory sequence provides Chaplin

the opportunity to score directly to his balletic motions. I must suggest here that at least some of the

themes, or at least the rhythm and flow of the score must have been in

Chaplin’s mind as he shot much of this segment.

In particular, the second factory segment, in which Charlie has his

breakdown, is scored so closely that it appears to have been performed to the

music.

At Bench 5 of the Electro Steel Corp., Charlie

tightens his nuts to the beat of the music, which clanks crazily to the sounds

of industry. The chromatically moving

strings represent the bee that distracts

him. In the washroom, an elegant waltz characterizes Charlie’s short-lived

leisure.

When the workers break for lunch, the music follows

Charlie’s movements as he jerks involuntarily to the muscle memory his job has

created, then Chaplin gives us a comic, plodding European melody that is called

‘At the Picture’ in the soundtrack album

which supports by juxtaposition Chaplin’s attempts to eat his lunch

The playful music that seems to symbolize the

feeding machine is increasingly drowned out as the contraption

malfunctions. Chaplin had to deal with

sound effects much more than he had to in CITY LIGHTS and he shows his command

of the medium by letting the effect take over when necessary.

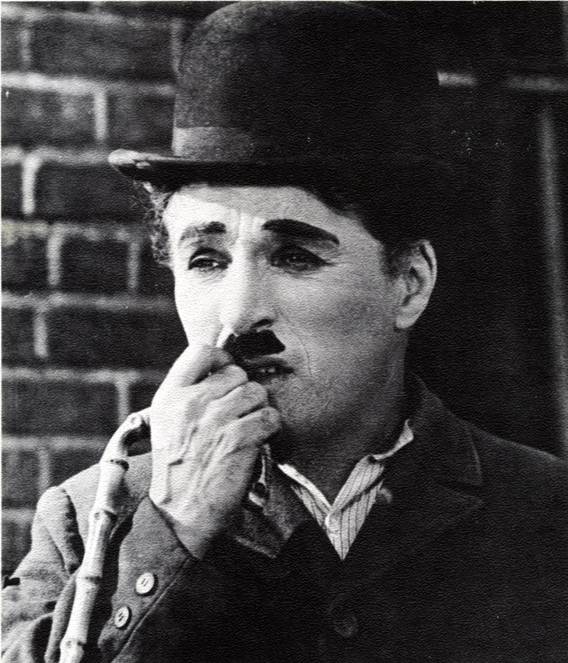

Charlie Goes Crazy with Tiny Sanford

and Heinie

Conklin (aka Charlie Lynn)

The second factory

sequence is the most ballet like in the film. Chaplin’s breakdown begins as the speed of

his conveyer belt (and that of the music) increases to a point where he cannot

keep up and the machine swallows him whole to the accompaniment of a charming,

mechanical, music box like moment in the otherwise frenetic theme. He’s spat out again as the music seems to

reverse itself, and exits the chute as a dancer, performing a mad ballet using

his wrenches to tighten everything in sight, actions followed closely by

musical hits or stingers. His chases of

the blonde secretary through the factory and of the buxom woman outside are

both accompanied by music that seems to represent those characters. His chase back into the factory continues the

ballet at an increasingly mad pace. A

variation of the ‘fate’ theme first heard in the titles, heralds his capture

and his parting shots from the oilcan are underlined and enhanced by the music.

Charlie’s release from the hospital is made

foreboding by the reuse of the fate theme

which segues into “Hallelujah, I’m A Bum’, an IWW worker’s rights song from

1908 with lyrics by Harry McClintock that had been written to the melody of a

popular hymn from 1863, “Revive Us Again”.

The tune seems particularly right for the Tramp character, as he wanders

the streets. It grows into a military

march as Charlie accidentally becomes the leader of the protest and becomes

almost an alarm upon the arrival of the police.

Paulette

Goddard as the Gamin

The Gamin is introduced by a four-note fanfare that will announce her appearance

throughout the film. It is followed by a scurrying theme reminiscent of

Prokofiev that supports her banana stealing actions. We hear her next theme, the more sentimental

“The Gamin”, as she comes home with her

booty, which continues as she comforts her unemployed father. The theme

suggests the irony of the father’s situation juxtaposed against the Gamin’s

cheery spirit.

The music in the prison scene is based on the march

we hear at the beginning of the segment.

It transmogrifies into a jaunty European sounding two-step as Charlie

meets his cellmate and continues into the mess hall scene, in which Charlie

inadvertently gets dosed with cocaine.

It rarely “mickey-mouses” the action (a temptation succumbed to by many

composers who wrote for cartoons), but underscores Charlie’s reactions with

mood and feeling rather than musical shots.

The jailbreak scene is appropriately underscored with tense active

music. When Charlie foils the escapees,

there is a musical quote of the “Prisoner’s Song” (“If I had the wings of an

angel, over these prison walls I would fly”).

The fate theme introduces ‘Trouble with the Unemployed”, transforms

into a gentler variation when the Gamin appears, and follows the scene through

her discovery of her murdered father. A

mournful tune plays while the authorities deal with the Gamin’s younger

siblings, but the Gamin fanfare telegraphs her intention to escape.

The washroom waltz from the factory is reprised as

we learn that Charlie is to be released from prison. The starchy Minister and his wife are

introduced by a comedic theme based on the prison march, but most of the scene

is played without music to make room for all the stomach gurgles and dog barks

in the sound effects track.

The fate theme appears again as Charlie is about to

be released into the cruel world, this time in a tentative, hesitant mood. Charlie’s short-lived boat building work is

performed to the breezy “Charlie and the Warden” (as it is called on the

soundtrack album). It is one of the

nicer melodies in the score having a slightly eastern European feel. It segues into “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum” after

Charlie makes his fatal mistake with the wedge.

The Gamin is introduced with her fanfare again,

which gives way to the beautiful pathos of “Alone and Hungry”. Her “hurry” theme is used again as she steals

the bread, and is interspersed with the previous poignant theme as Charlie

confesses to her crime. His efforts to

get himself arrested are underscored first by a new theme and then with a

reprise of the washroom waltz. In the

paddy wagon and during the escape we hear his prison theme, “Alone and Hungry”, the Gamin hurry theme

and the fate theme all repeated.

We get our first exposure to the wonderful “Smile”, with its hopeful and sentimental

mood underscoring the new couple as they sit by the side of the road. The dream sequence is backed by an

appropriately fantasy like theme.

Chaplin’s “In

the City”, a cheery tune with jazzy touches, a reworking of the boat-building theme,

supports Charlie’s new job in the department store. For the skating scene Chaplin goes against type

by not giving us a waltz theme until after the Gamin rescues him from the

precipice. Chaplin’s lovely “Valse” carries forward to accompany the

Gamin’s trying on the fur coat. The

Gamin music returns when Charlie puts her to bed.

The thieves’ introduction is well served by a

“sneak” theme, and when the action starts, a variation on the restaurant scene

music is used. The fate theme reappears

in a kind of drunken variant. When

Charlie is discovered under the cloth samples, there is a musical quotation of

“How Dry I Am”, and his arrest reprises the ‘Hallelujah” music again.

“Ten Days”

accompanies Charlie’s new home with Paulette.

Its graceful and cheery theme provides a contrast to the shabby

surroundings. The fate theme strongly

heralds the news of the factory reopening and the industrial theme of the

film’s opening plays as Charlie hurries to work.

A new march-like tune accompanies Charlie’s work

with Conklin and has a mechanical feel that well represents the machine in

motion. The lunch break is taken to the

tune of the European sounding “At the Picture” (whose title makes no sense

unless there was a movie theater scene cut from the original version for which

the theme was used). ‘Hallelujah…”

briefly reappears as Charlie and

One of the most charming melodies in the film

complements the Gamin’s street dance

to the calliope. It seems to be

something akin to what Chaplin would have heard as a boy in the

Charlie’s job

interview music is very clever as it mimics the dialog and characters in

the scene. The low strings and winds

represent Bergman’s manager and the high strings and flutes back the Gamin’s

lines as the oboe haltingly plays Charlie’s hesitant replies.

The nightclub segment is scored with the

klezmer-like tune called ‘Later That Night”

on the soundtrack album. Increasingly

frantic dance tunes play in the club as Charlie tries to deliver the duck to

his irate customer. The band plays a

varsity fight song when the football players make their entrance. The singing waiters introduce themselves in music

and begin their performance of ‘In the Evening by the Moonlight.”

Charlie’s performance of Leo Daniderff’s classic “Je

cherche après Titine” is so superbly pantomimed that, despite Chaplin’s

nonsense lyrics, one is totally aware of the story of the song. The lyrics, combining elements of French,

Italian and Russian are below, transliterated as best I can:

Titina (Je Cherche apres Titine)

Music

by Leo Daniderff. Nonsense lyrics by

Chaplin

Se

Bella ciu satore, je notre so cafore

Je

notre si cavore, je la tu, la ti, la tua

La spinach

o la busho, cigaretto porta

Ce

rakish spagaletto, si la tu, la ti, la tua

Senora

Pilasina, voulez vous le taximeter,

Le

zionta sous la sita, tu la tu, la tu, la wa

Se

muntya si la moora, la sontya so gravora

La zontya

(kiss) comme sora, (slap) Je la poose a ti la tua

Je

notre so la mina, je notre so cosina

Je le

se tro savita, je la tuss a vi la tua

Se

motra so la sonta, chi vossa la travonta

Les

zosha si katonta, (kiss) tra la la la, la la la

Les de,

le ce, pawnbroka, Lee de ce peu how mucha

Lee ze

contess e kroke, punka wa la, punka wa

The couple escapes from the authorities to another

European dance type tune, and at dawn decide to go it together to the final

version of “Smile”, which so well represents the dialog – “Buck up – never say

die. We’ll get along!” and likely gets

its name from Charlie’s mimed encouragement of the Gamin to smile.

The Modern Times soundtrack lp was released on the

United Artists label in 1959 to coincide with the film’s re-release in the

The Magical Ending